Arkansas isn’t ditching voting machines for paper ballots, despite claims online

W.J. Monagle votes in the Arkansas primary election at Saint Mark’s Baptist church in Little Rock, Ark., on Tuesday, May 24, 2022. The Associated Press on Friday, Sept. 1, 2023 reported on social media posts falsely claiming that Arkansas is switching to hand-marked paper ballots statewide. (Stephen Swofford/The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette via AP)

CLAIM: Arkansas is switching to election ballots that are marked by hand rather than by machine.

AP’S ASSESSMENT: False. There’s been no statewide change in how voters cast ballots, elections officials and voter rights groups in Arkansas say.. Residents will still continue to use voting machines in nearly every county in the state. One rural county recently approved a plan to start using paper ballots that voters must mark by hand, and a final vote on that decision is expected later this month.

THE FACTS: Social media users are claiming Arkansas is ditching voting machines in favor of old school pen-and-paper.

“BREAKING: Arkansas will use hand-marked paper ballots in all future elections,” one user wrote on X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter. “Do you support this?”

But state officials have issued no such requirement and votes will continue to be cast on machines in most local jurisdictions, as they have for years.

“This is 100% false information,” Chris Powell, a spokesperson for Arkansas Secretary of State John Thurston’s office, wrote in an email this week.

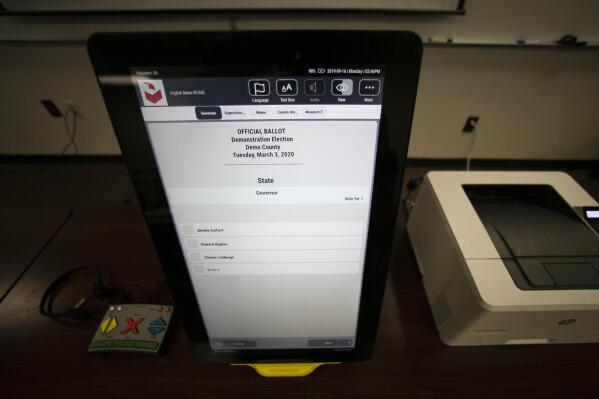

The vast majority of the state will continue to use the ES&S ExpressVote system for upcoming elections, he said.

Under the current process, voters select their candidates on a touch-screen display. The machine then makes corresponding marks on a paper ballot, which is printed out and run through a ballot scanner, which tabulates the vote.

Conrad Reynolds, CEO of the Arkansas Voter Integrity Initiative, a local group that’s been pushing for counties to switch to hand-marked and hand-counted ballots, confirmed the posts are spreading misinformation.

“There is no law or anything at this point saying that the state will go to a paper ballot, period,” he said by phone. “That is not true.”

Efforts to bring back hand-marked and hand-counted paper ballots gained momentum after the 2020 election, fueled by conspiracy theories that voting systems were manipulated, leading to former President Donald Trump’s defeat.

But election experts say hand counts take longer and are far less reliable than counting with machines.

In Arkansas, just one of the state’s 75 counties has so far decided to switch back to more traditional voting methods, according to Powell and Reynolds.

Election commissioners in Searcy County, a rural district with a population of less than 8,000, voted last month to begin using paper ballots that voters fill-in by hand. However that decision still requires a second vote to be finalized.

Meanwhile, Cleburne County voted earlier this year to adopt a similar hand-marked ballot process, but the county of nearly 25,000 residents rescinded the decision just months later.

Arkansas lawmakers also passed a law this year requiring any counties that switch to hand-marked paper ballots to first tally ballots by machine in order to quickly turn around the initial election results. The ballots can be counted by hand later for the official results.

The new law also makes it clear that any costs counties incur for using hand-marked paper ballots, such as additional spending on labor and materials, won’t be reimbursed by the state, as is the case with other election expenses.

___

This is part of AP’s effort to address widely shared misinformation, including work with outside companies and organizations to add factual context to misleading content that is circulating online. Learn more about fact-checking at AP.